HAMPIÐJAN BALTIC

Hjörtur Erlendsson, managing director

When Hampidjan arrived in Lithuania in 2003 after acquiring netting manufacturer Utzon, there was a workforce of a hundred already there. The company was quickly renamed Hampidjan Baltic and the premises were doubled in size to their present 21,500 square metres, with twine and rope manufacturing and a net loft established in the additional space between 2004 and 2006. Now Hampidjan Baltic has around 280 staff.

Did the financial crash have the same impact on Lithuania as it did in Iceland?

‘Yes, and if anything, the effects were worse. In sales terms, the crash didn’t affect us on the domestic market, simply because very little of Hampidjan Baltic’s production is sold in Lithuania or the other Baltic States. Then there is only around 10% of production that leaves here as direct sales while the other 90% goes through the sales department in Reykjavík. What we supply as direct sales goes to the Baltic region and to Holland. The reason for this is that Utzon sold a good deal of netting to Holland and we inherited those business contacts. Other contacts were transferred to the sales department in Iceland.’

Demand for super-strength

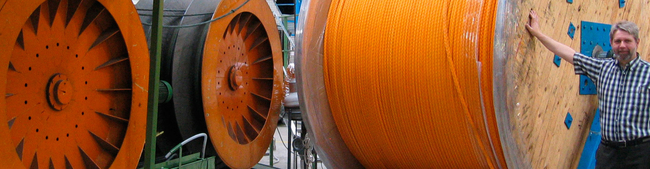

There have been some fundamental changes in fishing gear technology in recent years and decades, in which Hampidjan Baltic has taken a leading role. There has been a great deal of development in ropes and cables, and Hjörtur Erlendsson said that their production of conventional three-stranded rope has been scaled back with the focus firmly on high-tech products such as Helix ropes for pelagic trawl gear and Dynice super-strength ropes, as well as a variety of specialised ropes and cables for the offshore sector.

‘At Hampidjan our first meetings with DSM, which owns and produces the Dyneema raw material used to make Dynice products, was in 1986, just two years after the company had started its own production of the fibres. We obtained some of the raw material and our technicians started investigating how this super-strength material could be used in fishing gears. Those early experiments and the extensive development work since then has been the basis for approximately 60% of the values that are created at Hampidjan Baltic being linked in one way or another to producing Dynice super-strength ropes,’ Hjörtur Erlendsson said, commenting that Hampidjan Baltic’s activities can be divided into three main areas. These are rope production, netting production and the net loft. Rope production includes a wide variety of products and netting is produced in nylon and PE. The net loft operates as a department of the net loft in Iceland, and also does a great deal of work for Cosmos Trawl in Denmark, which is also part of the Hampidjan Group.

According to Hjörtur Erlendsson, production of materials for fishing gear forms the bulk of Hampidjan Baltic’s activities, also offering significant future possibilities, particularly with Dynice Warps and the Dynice Data sounder cable. But he said that one of the real potential growth areas at present is the production of a variety of Dynice products for the offshore industry that includes services to the oil and gas industries. Then there is also the significant upswing in specialist ropes used for seismic survey applications. Hampidjan has seen some important successes in this field and now has the largest market share of the companies serving this industry. This calls for towing cables for the array that a seismic survey vessel tows behind it, and an intermediate line between the hydrophone streamers that are used in surveys, as well as strops running to the deflector that functions in much the same way as a trawl door.

Constant development

The factory in Lithuania operates around the clock with three shifts across a five-day week, apart from the department producing super-strength materials, which has been running a 24 hour timetable seven days a week due to the high demand for its products. An important part of the department is a well-equipped research facility employing nine specialists who are able to do all their fishing gear and engineering work in 3D.

The emphasis on development has been at the core of Hampidjan’s work, along with its focus on producing its own materials. Hjörtur Erlendsson commented that in recent years there has also been a strong focus on patenting the company’s products and ideas.

‘We have always been in a position on the fishing gear market in which we receive raw materials, ranging from plastic floats to Dyneema fibres, that we get from suppliers and from these we come up with completed fishing gear. This means that not only have we had to do extensive product development, we have also had to develop the equipment needed for all this. As far as I’m aware, this is a unique situation, which has also given us the opportunity to build ourselves a special place on the market with products that nobody else can supply. If we want to modify or improve some aspect of the fishing gear, the whole process is down to us with no need to consult anyone outside. This in turn means that we can respond very rapidly when we see an opportunity to develop something new or to improve an existing product.’

Competition never sleeps

There is some stiff competition on the fishing gear market, and no less competition on the market that the oil business has generated. Hampidjan has sales all over the world and the question for Hjörtur Erlendsson is where the possibilities for the factory in Lithuania lie in the coming years.

‘Hampidjan has increased its market share in Ireland, Denmark and Sweden, plus we are always doing better and better in Norway. The position of the factory in Lithuania is excellent for the European market. We can ship out goods that are in Holland twenty-six hours later and we can get a container to Iceland in eight days if we need to. As far as the factory itself is concerned, we have invested heavily in production equipment and not least in rope braiders for Dyneema. We have the largest braiders in Europe for 12-strand rope and there are only three of these in existence worldwide. We can braid rope up to 200mm and the breaking strength of a Dyneema rope of this kind is as much as 2800 tonnes. As far as production is concerned, we still have the option of adding a considerable amount of production capacity without needing to extend the buildings. We can expect continuing competition in all areas, but we are in a prime position to continue making progress.’